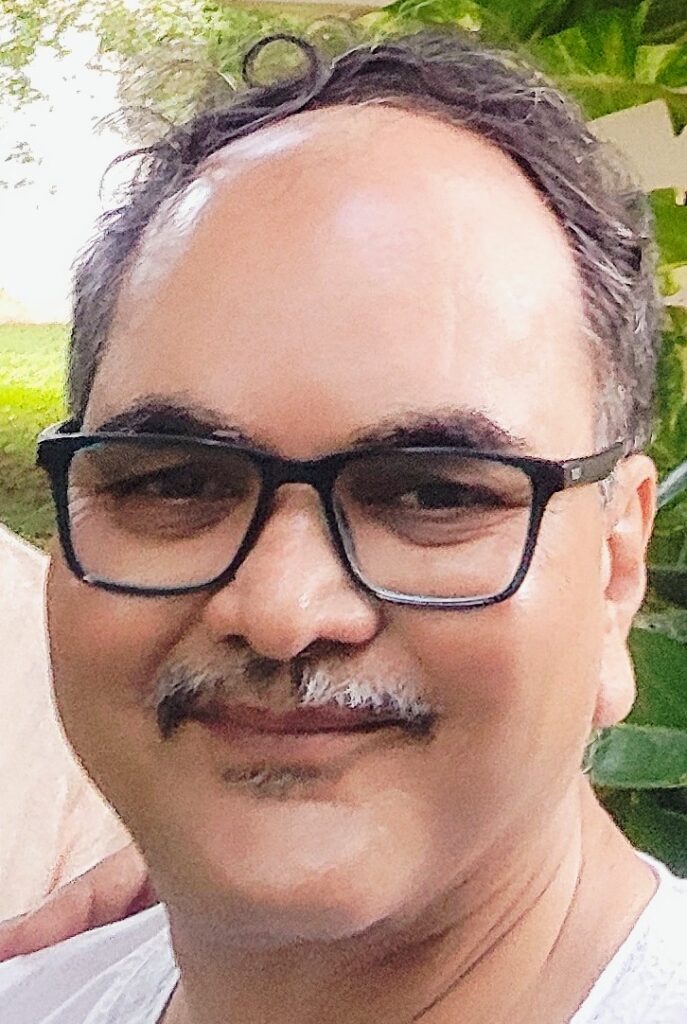

During an informal chat over dinner recently at KFI Vasant Vihar in Chennai, retreat participants heard an interesting story from Mukesh Srivastava. It was his own story and turned out to be gripping. Here is that story in his own words.

Life in Agra was quite interesting in early 20th century which has been described by Paul Brunton in his classic A search in Secret India. As I was growing up there in the 1970s, I encountered the practice of bhakti based on Surat Shabd Yoga, a special kind of Nad Yoga. Devotion to the guru was part of this and I was deeply ensconced in that world-view.

As I came to university education and was exposed to “higher learning”, I began to question everything. And in this endeavor, not only European literature and philosophy but our own Vivekananda and Osho contributed significantly. I was alone, my parents had passed away and no one else could understand.

In the next stage of my career, I found myself studying at CIEFL Hyderabad which was at that time one of the best centers of higher education in India. As I was keenly interested in Vivekananda, I decided to undertake research for an M.Litt. thesis under a reputed professor. Here again, I was in for a rude shock because I was persuaded to look at religious discourse in particular, and life in general, through a totally academic ‘lens’.

While this new learning was interesting, its insistence on total nihilism and absence of any fundamental spiritual understanding shook me from within! So intense was this inner struggle and so isolated was I that I seriously contemplated suicide. I remember at that time writing a letter to Krishnamurti Foundation India, Vasant Vihar in 1986 with a proposal to carry out ‘research’ in search for truth. I got a reply from the secretary asking me to meet him at Vasant Vihar. Unfortunately, I could not travel to Madras and so the meeting didn’t happen.

As I was growing restless, I happened to meet a senior professor who was well versed with both J. Krishnamurti and Sri Ramana Maharshi and that soothed my nerves somewhat. The thought of suicide evaporated and I took up a job as sub-editor in a publishing company in Hyderabad. The demands of a job like that, the dreary routine and the so-called discipline, the utterly futile gossip and hypocrisies of the work place exhausted me completely. It was at this time that I picked up Krishnamurti again for serious reading. While I found his writings fascinating, Krishnaji’s teachings did not seem to offer relief from my intense suffering at that time.

The communist world-view, in which I was intellectually trained for about ten years, had died a natural death and there was a vacuum. In that period of despondency, I experimented with drugs and they produced some totally out-of-the-world experiences. But I knew very well that such bursts of ecstasy would prove to be destructive. Fortunately, I quit.

A chance interaction with the Director of IIM Ahmedabad resulted in my joining there. I was required to apply insights derived from literature and philosophy to educational innovation and policy. However, none of that ever happened as the Director went abroad and the nature of my job changed drastically. I began to feel stifled in a world of business management, finance and corporate training. So without much ado, I quit that place too and was looking at a grim future!

At that time in Ahmedabad, I recall seeing a small write-up in the Times of India column about Krishnamurti dialogue meetings on Sunday mornings. My eyes lit up instantly. As I reached the place and knocked at the door, an elderly gentleman opened the door and asked “Where are the others”? I replied that I was alone. The man asked: “Have you read my books on Krishnamurti?” I said, No! He then paused and seemed to show very little interest in talking further.

Ahmedabad became a rather dry place but I had nowhere to go. So I remained there for some time. My correspondence with a Professor at the University of Chicago opened up a fresh possibility. He invited me to teach Indian Literature at the university of Chicago, but when I reached there, he himself had left for a new project in India. At the university, I felt somewhat at home as I enjoyed the subject and there was the possibility of ‘creative living’. This feeling of being ‘at home’ was shattered soon as a British official, who became my boss, developed a terrible misunderstanding. I was asked to quit even though my students seemed to enjoy thoroughly the discussions we had in the classrooms.

Getting back to India, I thought I should flow from moment to moment and let life take its own course. So I often found myself living in the mountain hills, forests, even in slums as I ran out of money, until I came upon a Hindu monastery in Amarkantak, M.P. I requested the Swami in ochre robes to grant me permission to live there on a modest payment to which he agreed. So here I spent more than two years in the forests.

I had no illusion of leading a ‘religious ’life and least of all becoming a ‘monk’ and yet life had thrown me by chance in the company of monks. I wanted to carry on as long as possible without offering resistance. However, I would be lying if I said I was not upset. There were indeed moments of extreme anguish and depression and the suicidal tendencies surfaced again. But in saner moments, I realized that this is the real test of reading Krishnamurti and other great seers! Live life as it comes without resistance and if death comes welcome it!

Here I had the occasion to observe the life of monks from close quarters; their daily gossip, fear, excitement, frustration and even occasional quarrels leading to violence. Once I found a senior monk who was the vice president of the order visiting a famous astrologer. The astrologer’s son told me that the monk wanted to know when he would become President and what kind of remedies he should undertake to propitiate the stars!

At last, another chance happening brought me to my current job in Bhopal where I have lived without a break. I realized that no matter where you go, you will have to confront the same pattern of forces; thwarted ambitions, jealousy, greed, arrogance, and the impulse to ‘become’ someone. In short the corruption of all kinds, not only outside but also within oneself. There is thus no safe place in the world!

With this realization, not just verbally but actually, one may be able to live quietly amidst all the sound and fury and not be shaken. The realization that you own nothing, not even what you call your body and mind, is very liberating. You may then be able to stand in a blazing sun that leaves no shadows.

In conclusion, one may say with Shakespeare in The Tempest:

We are such stuff as dreams are made of

And our little lives are rounded with a sleep.

Or with Kabir:

O Friend! Search on while you are alive.

If your bonds are not broken now,

What hope of freedom after death?

Learn the art of living with death

And then you have arrived home!

Beutiful write up and honest descriptions of the writer’s life.

Yes, the “apparent” narrative of this man’s life unfolded in authentic and naturally transformative ways. The effort of a “me” seems to have been finally replaced by a natural flowing into the unknowable yet precious qualities that can be perceived only by means of the trials and tribulations of such an organic process as described by him. Thank you.

सत् चित् आनन्दम्।।

“K” once said to (1) observe without centre (2) observe without naming the observed. However it requires tremendous discipline but if observed so, A VERY STRANGE THING WILL HAPPEN “

Thanks Mukesh, very interesting journey well articulated.

Best wishes

Vishwanath

Thanks Mukesh, very interesting journey well articulated.

Definitely an engaging read. To stop looking through the lens of fear, any lens as a matter of fact, and look at life as it is, while embracing it’s non-linearities, is perhaps the only way to be alive, while death remains a constant companion.

.