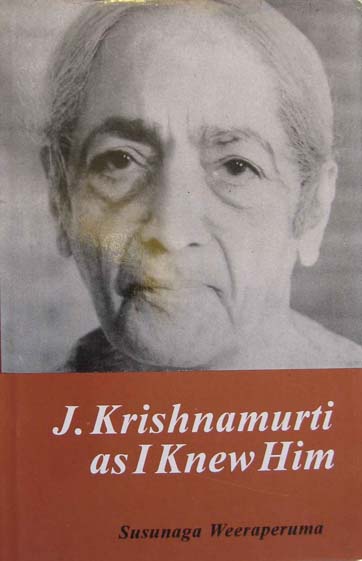

Extract from the book 'J Krishnamurti as I knew him' by Susunaga Weeraperuma. He narrates a conversation he had with K.

Susunaga Weeraperuma: Krishnaji, I much enjoyed the concert last night. I have come to India to listen to such melodious music. It was such a treat.

Jiddu Krishnamurti: Yes. It was a marvellous performance.

Weeraperuma: What puzzles me is why you participated in the chanting of bhajans. I was observing you very closely. You were in the front row and chanting vedic hymns! I am not against Vedic hymns for I love them very much myself. But please may I ask why you have often expressed strong disapproval of any kind of worship? You condemn worship but yesterday you were joining others in worship!

Krishnamurti: One can listen to an enchanting bhajan and still not be influenced by its ideas. It is possible to listen to a Sloka or Bhajan and experience the magical effects of the sounds on the mind and totally ignore all the myths, legends, beliefs and concepts that are so much part of the Indian classical tradition. Have you tried enjoying a Meera bhajan without believing in Krishna or any deity?

Weeraperuma: I think a Bhajan becomes more meaningful when one is aware that it is addressed to a particular deity. A bhajan is a devotional outpouring of the heart.

Krishnamurti: Oh, no! I wouldn’t call that devotion. Real devotion is motiveless. It is a state of not asking anything. But when you stand before an altar and offer puja and then ask favours in return, that is psychological bribery, isn’t that so? You try to bargain with the deity. You are telling the deity: “I am offering you this and you must provide me with that in return.” But real devotion is a state in which the mind is not focussed on any particular object, person, deity, belief or idea.

Weeraperuma: Are you saying that a true devotee has an objectless state of mind?

Krishnamurti: Exactly. As I was saying, the right way to listen to any hymn or devotional chant is to experience only the sound – its movements of melancholic supplication and joyous ecstasy, and just remain there, not allowing your mind to get conditioned by the particular religious ideas and beliefs that nearly always go hand in hand with the music. Then you will find that all kinds of devotional music are fundamentally the same.

Weeraperuma: Shall I organize a concert of Western classical music for you?

Krishnamurti: Don’t trouble yourself. I will have many opportunities of listening to Western classical music when I go to Europe.

Weeraperuma: I’m fond of Bach, Beethoven and Handel.

Krishnamurti: I also like those composers. Do you follow what I am saying? If you listen carefully you will find that every kind of devotional music, regardless of where in the world it originated in, has certain common elements. What are these common elements? Haven’t you noticed that all devotional music is a kind of asking, crying, begging?

Weeraperuma: That quality makes the music very touching. I understand what you are saying.

Krishnamurti: I wonder whether you have ever listened to a child crying. Have you?

Weeraperuma: The noise of children screaming and crying gets on my nerves! I want to run away!

Krishnamurti: If you have really listened to a child crying with all your heart and mind, as I have done, not listening partiality but listening fully with undivided attention, then you will also feel like crying. You will want to hold the hand of the child and join him or her in the crying. Unless you have a pure heart you will not be capable of doing that. I am describing the state of true devotion – not the nonsensical devotion of a stupid mind that offers flowers and incense to an image made by the hand or the mind.

Weeraperuma: Would you call that pure bhakti?

Krishnamurti: The name is not important. You may give it any name you like but do you have that quality of feeling?

Weeraperuma: I often go to concerts but the difficulty is that after listening to the first few bars of a song my mind starts wandering.

Krishnamurti: Then wander with your mind and find out why your attention is shifting from one thing to another.

Weeraperuma: What you are suggesting sounds excellent but I have tried it out in practice and often I am unsuccessful.

Krishnamurti: Keep on trying and never give up.

Weeraperuma: Somewhere in your writings you have stated that music is to be found not in the notes but in the interval between the notes. I have failed to grasp the full significance of your statement.

Krishnamurti: Notes in themselves are quite meaningless, aren’t they? Similarly, when you read a book, the words in themselves have no meaning at all. Notes and words are meaningless sounds. It is in the interval between words, in the state of silence between the words, that you capture the meaning of what the writer is trying to convey. So don’t get lost in the technical side of music.

To appreciate a piece of music it is not absolutely essential to have the ability to read it. Understanding comes only when the mind is silent. And don’t regard music as an escape or as a drug that may induce silence. That silence comes naturally, effortlessly, when you understand. Music is born in that silence. That silence is the source of all creation. That primordial silence has no beginning and no end. That silence, the eternal, is beyond the reach of the intellect.

Above was an extract from the book 'J Krishnamurti as I knew him' by Susunaga Weeraperuma.

I am a devotee of the True Nature of what is and with affectionate awareness there is a spontaneous deconstruction of maladaptive attachments beliefs and values.

Then the child’s crying becomes that of my own. The music echoes my own stillness. The result is accepting the world as it is when we show up.

Thank you Susunaga